|

||||||

English |

Nederlands |

Deutsch |

по-русски |

|||

|

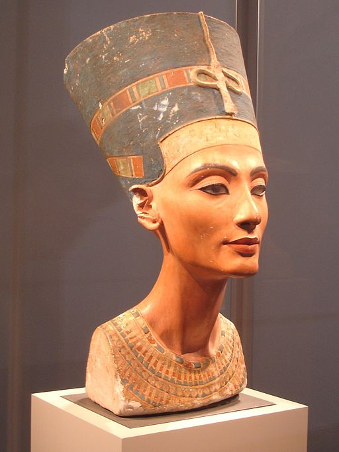

DOUBLE STANDARDS IN HERITAGE RESTITUTION~ let's de-colonize our western minds! ~different standards Why do we apply different standards to restitution claims from former colonies and to restitution claims from victims of the Nazi regime lootings? How little of us have cried out against the auctioning at Christie's of objects looted from the Summer Palace in Beijing during the Opium wars, but how many of us have felt scandalized about the display in the Thyssen Museum of a Pisarro looted during the Second World War? Both cases concern precious cultural objects, from funerary masks or sculptures to pictures, removed from their legitimate owner by a foreign regime during episodes of violence to appear somewhere else in the hands of some new owner. The cultural objects looted during colonialism that are subject to restitution claims are of a very varied nature. From jewels to funeral objects, masks, sculptures, ritual objects or even human remains, what matters is that these objects represent a culture, the creative genius of a people, and have been removed from the place where they had most signification. Efforts for returning pieces taken during colonial rule are far less numerous and successful than those directed at returning Nazi looted art. Is this a sign that in the barometer of the public opinion the moral duty to grant former colonies' right to recover what is rightfully theirs is less important that the moral obligation to atone for the lootings of the Nazi regime? The public sphere reflects our moral duplicity, as the cases of restitution claims from former colonies are barely discussed by the mass press and within the sphere of public debate. After all, where are the movies concerning restitution of looted colonial objects in contrast to the blockbusters The woman in Gold or The monuments men? Where are the movies about the efforts of Egypt's or India's lawyers and experts to get back the Koh I Noor or the Bust of Nefertiti, kept respectively at the Tower of London and the Neues Museum in Berlin? We need to open our eyes to these double standards, which become evident when comparing the efforts taken by international organisations, national governments and museums towards the restitutions of Nazi and of colonial-looted objects. legality and morality During the twentieth century, cultural objects were looted from their rightful owners in several circumstances. Among these, we will focus on the pieces of art which were unjustly taken by the Nazis and on those seized by European Countries from their colonial subjects. A fundamental distinction has to be pointed out: at the time when these facts occurred, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 posed a prohibition on its Parties -among which we can find the main European Powers- to loot civilians properties in territories under their occupations. As a consequence, the actions of the Nazi regime in regarding to art pieces owned by Jewish people were considered to be illegal albeit morally supported by the ideology of the regime. Nevertheless, the situation is different concerning colonial goods: back at that time, a vague prohibition related to their seizure existed. As a consequence, the legal protection which they received was in no way comparable to the one of the cultural properties possessed by European owners. international frameworks Since the 1990's public interest in Nazis' cultural spoliation has grown so strong, that on top of existing instruments, new ones were introduced. In 1998, the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi Confiscated Art were adopted by an international forum, including countries such as Austria, France, and the United States of America. This declaration expresses the commitment of several western countries to identify and restitute the works of art which had been confiscated by the Nazis during WWII. On an European sphere, the Washington Convention influenced the final declaration of the Vilnius International Forum on Holocaust-Era Spoliated Cultural Assets in 2000. time-prescription An important common denominator of these international instruments is that they re-state rules which already existed at the time when the relevant crimes were committed, with an important addendum: they erase any statutory limitations, time-prescription, which could exist on, for instance, restitution claims. In practice, this concept entails that the rules and provisions of these agreements will also be applicable to events which took place years before their adoption. Despite the fact that the Nazi lootings happened almost 50 years before the drafting of the instrument, it seemed that nations around the world still felt compelled to redress what they felt was a profound injustice. They acknowledged that the looted art should have been returned to their previous, rightful owners, and to this end they were ready to draft instruments with a retroactive applicability. It seems logical then, that if the same wrong actions (i.e. looting and pillaging) were committed to former colonies, the same principle of no-statutory limitation, no time-prescription, would apply. But is it in fact applied? The answer, unfortunately, is no. The lack of an international legal framework for the restitution of colonial objects bears witness that our western minds are not yet free of a "colonial" mindset, as we do not recognize the equality of rights of former colonies to enjoy their cultural heritage and we do not see the immorality of these double standards. Indeed, a major example of double standards concerning restitution refers to the issue of statutory limitation of international instruments. Whereas already since the enactment of the London Declaration in 1945, and confirmed by the Washington principles, the international community and national restitution committees recognize that no time-prescription could influence claims regarding the restitution of Nazi-looted art, former colonizers made sure during the drafting phase that the UNESCO Convention of 1970 did not include any similar clause. Therefore, no recourse is offered to peoples who were unjustly deprived of their cultural objects before the enactment of the Convention, that is, during the colonial rule. This deprivation was denounced as unfair during the UN General 1976 Assembly but nothing was ever undertaken to improve the situation. Even more astonishing is to notice that no binding instrument whatsoever has ever been adopted to deal with the issue of colonial-object restitution. state succession State succession of cultural property after independence has been a widely applied principle and was practiced in an European context since the nineteenth century. To former colonies the principle of state succession was in most cases not applied. This means that the newly independent states were disowned from property that belonged to their people. The International Law Commission Report noted this phenomenon in 1981. This report inspired the Vienna Convention of 1983, which however never entered into force and therefore had no practical effect in improving the existing legal framework for restitution of colonial pieces. a national framework - The Netherlands Also on a national level unwillingness to restitute colonial art and artefacts is institutionalised. Let's take The Netherlands as example. In November 2001, the Dutch State Secretary of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCenW) officially set up the Netherlands Advisory Committee on the assessment of restitution applications for items of cultural value and Second World War. Commonly known as Restitutie Commissie, this committee advices the State Secretary of OCenW in relation to individual applications for the restitution of cultural properties from which the owner was involuntarily separated due to Nazi-related circumstances. Furthermore, private individuals may also file a claim with the Commissie to request further investigation and advice on allegedly-stolen art works. This alternative dispute resolution method has been in function for several years. Several pieces of Nazis-stolen art have been rendered to their owners, such as the famous Woman playing a lute. But did the Dutch government ratify a similar agreement with, for example, its former colony Indonesia? Once again, the answer is no. It seems like neither the public interest, nor the determination that the population and the Government of The Netherlands had (and still have) for Nazi-looted art reached the colonial cultural properties, since no instruments concerning its restitution have ever been adopted by the State. Restitution as a political instrument It is true that in a few cases, national governments have restituted colonial objects. Nevertheless, it always seemed clear that these actions were more due to an economic or political profit, rather than being morally and ethically motivated. For instance, it is widely known that the return to Libya from Italy of the Venus of Cyrene had been a strategic move destined to secure oil deals. Moreover, the restitution from France to Korea of the manuscripts from the royal archive was motivated by a wish of President Chirac of France to secure a contract for the construction of a high speed train railway. And what about museums? How do museums deal with Nazi-looted art, and how do they deal with colonial objects? The American Association of Museums was in 1999 the main promoter of the Guidelines Concerning the Unlawful Appropriation of Objects during the Nazi era. This soft-law, non-binding instrument strives to 'achieve excellence in ethical museum practices' by advising museums on how best fulfil their public trust responsibilities. In the UK, a special working group was set up by the National Museum Directors' Conference in 2008 with the task of examining the main the issues surrounding the looting of art pieces during the World War II period, concluding with a Statement of Principles and Proposed Actions, addressed to member institutions and which could decisively improve restitution-related practices. It seems incredible then, that the same museums, including the British Museum (London), the Getty Museum (US), the Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam) or the MET (New York), signed the Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal museums in 2002. This document is the embodiment of a very common museum response to requests of restitution of colonial objects: in a nutshell, a strong, resolute NO. The main argumentation of the Declaration is in fact that they are not under any duty to return these types of artefacts. On the contrary, they plead that colonial objects have been part of their collections for such a long time, that nowadays they have become part of their own heritage. Moreover, they claim that the circumstances of their acquisition, so far ago in history, cannot be measured by actual standards. Luckily, positive signals of changing attitudes towards restitutioncan be signalled in other museums. The Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, during an exhibition in 2012, encouraged its public to question whether the pieces exposed should be returned to their country of origin; and the Museum of Rouen, as a consequence of an initiative of the city major, returned the Head of a Maori Warrior to New Zealand. This could be a sign that museum practices are slowly changing. Nevertheless, no joint declaration of French, British or any other colonial museum has yet been made about their willingness to redress the removal of art pieces. Looting by consent? In more recent colonial history objects have not in fact been looted, but bought or collected with full consent of local authorities; however, probably not with full knowledge of the value these objects. The Pergamon Museum has plenty of archaeological objects, which were taken in agreement with local, primarily, Iraqi governments for scientific research and later public display. Such acts cannot be described as looting and should, in our opinion, not be subject to restitution claims unless they are retained against the will of the originating culture. In the same Pergamon museum we find the Ishtar Gate, one of the many cultural objects shipped to Europe as part of a larger trend of accumulation by European colonists across the Middle East, which has already sparked demands of restitution. Conclusion To sum up, are not these governmental, international, national rules and legislation together with museum practices and attitude towards colonial artefacts and public opinion in the West in complete contrast to the efforts to the redress of Nazi lootings? The answer can be only one: indeed, a different weight is attached when the deprived are from a western country compared to when the same injustice is bestowed on people of former colonies. Maastricht, July 2016

Alessandra Silva and Cecilia Cotero Torrecillas are students of the Maastricht Law Faculty and the Faculty of Social Sciences respectively. They participate in the inter-faculty MARBLE project Art and Law: the Legal status of cultural property - a comparative analysis. MARBLE stands for Maastricht research based learning. It is a programme which offers motivated and high-performing students the opportunity to broaden their knowledge in a particular area as well as to equip them with additional research skills. The MARBLE project Art and Law is coordinated by Prof. Hildegard Schneider and Vanessa Tünsmeyer and offered by the Maastricht Centre for Arts and Culture, Conservation and Heritage (MACCH). This article is the result of a collaboration of Murk Muller and the MARBLE students in the area of art law.

| ||||||

| Vervoer | Handel en Industrie | Contact | Colofon | |||

| Incasso Duitsland | Art Law | Netwerk | Anwaltsladen | |||

| Kosten Mahnverfahren | Duits procesrecht | DBLA | LEXML | |||

| Publicaties & Interviews | Duits contractrecht | FAQ | Doorzoek mmrecht.com | |||

| Brexit | Halal | Plezier | Murk Muller | |||